A man who carves truth into metal and walks with the weight of witness.

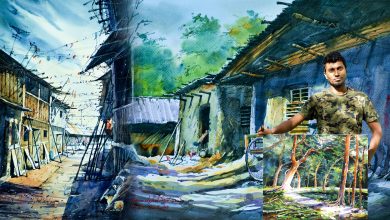

With the quiet intensity of someone who has lived several lifetimes in one, Fawaz Rob stands today as one of Bangladesh’s most compelling contemporary voices. A master printmaker for whom art is not merely a skill or profession. For him, art is a moral position. A form of resistance. A way of refusing silence.

Born in the windswept coast of Chittagong and shaped by years in San Francisco, Florence, and Dhaka, Fawaz moves between cultures, media, and philosophies with the ease of someone who belongs everywhere and nowhere. Yet the pulse of his art remains deeply and unmistakably Bangladeshi. Rooted in empathy. Anchored in history and driven by a profound responsibility to speak for those who cannot.

Fawaz’s conviction is simple and sharp as a needle: “If our art cannot speak the truth when it matters, then what good is it?

In a world where suffering is endlessly scrolled past, and tragedies dissolve into content, Fawaz believes art still has the power to interrupt, to slow us down, to make us feel, to force us to reckon. He traces this belief back to a single moment from childhood. At twelve years old, he encountered Norman Rockwell’s The Problem We All Live With. That painting did not simply impress him; it altered him. A single painting led him into years of reading, questioning, and understanding race, justice, and power. One image opened an entire moral universe. That

he says, is what art can do. Not decoration. Not performance. But awakening.

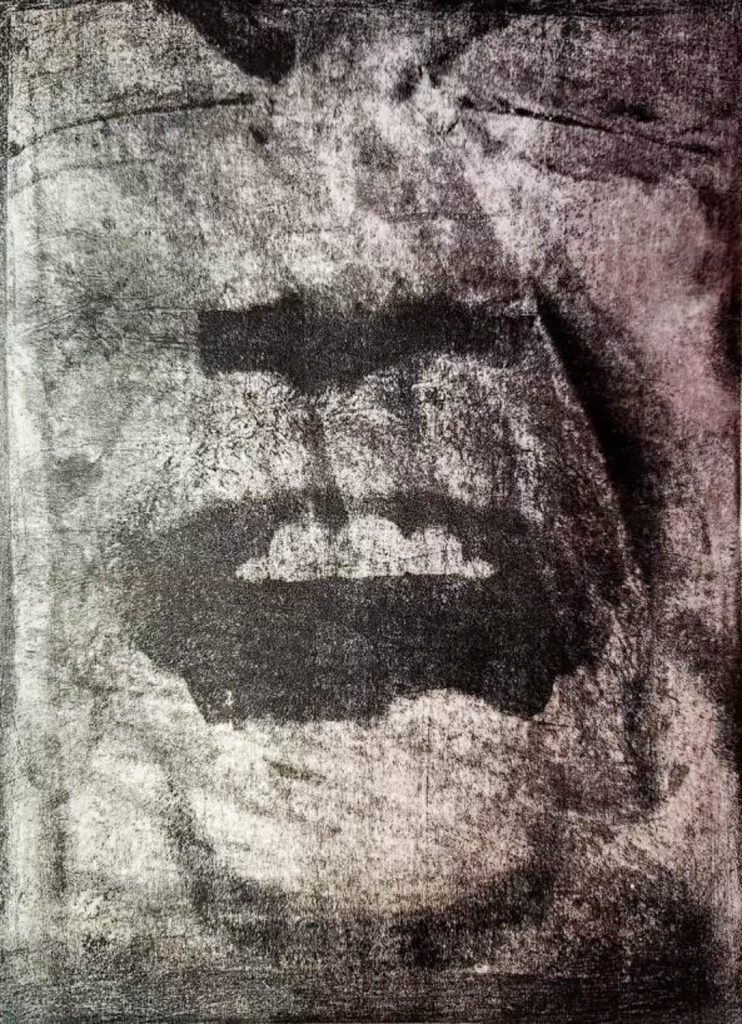

The most decisive turning point in Fawaz’s artistic journey was not found inside a gallery, but amid the mud, smoke, and fragile shelters of Cox’s Bazar. Working as a consultant during the early days of the Rohingya crisis, he witnessed suffering so raw it threatened to undo him. One image remains etched in his memory: a young girl, her leg pierced by a bullet, wandering through the camps in search of her parents. Around her, thousands of families walked with nowhere to go except away from the ashes of their homes. That image, he admits, cut through his soul.

For an artist who could have chosen a lifetime of technical mastery alone, drawing flowers, landscapes, and abstractions, this moment was inescapable. It was where art and activism collided. When imagination was not enough, when witnessing demanded action.

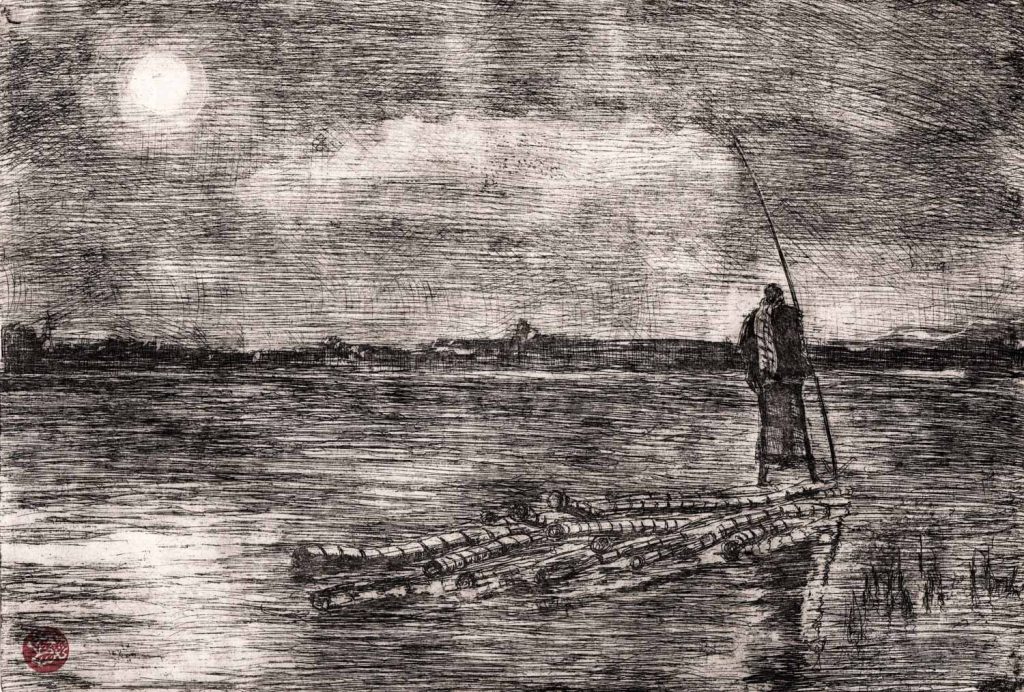

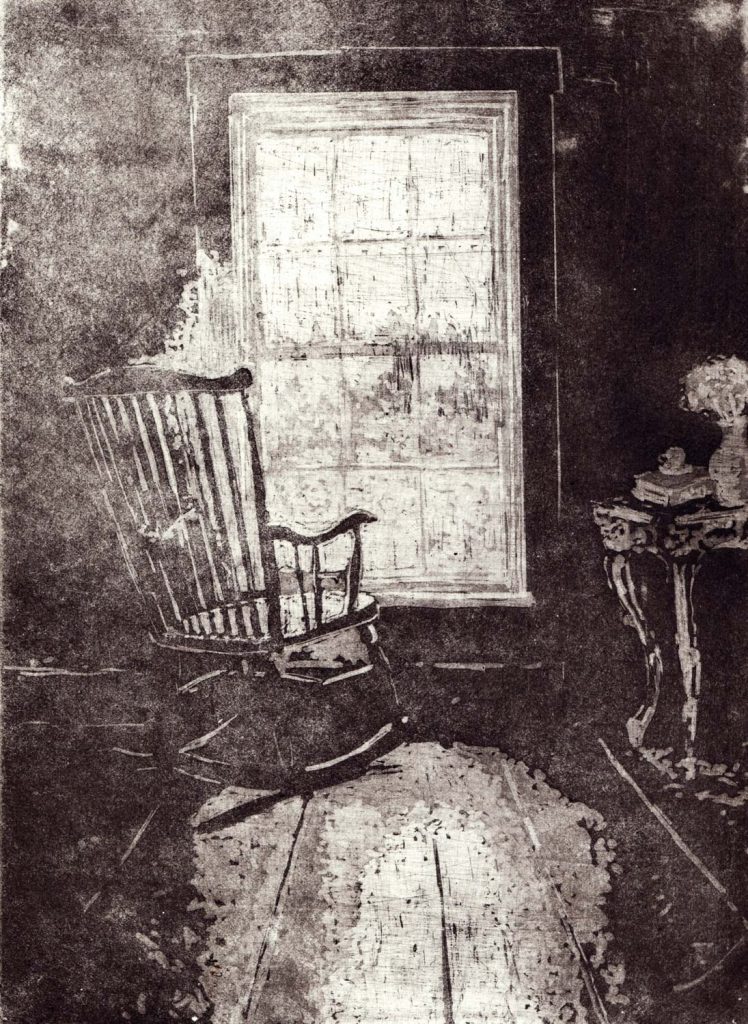

From that fracture emerged Long Walk Home, a print capturing the endless procession of Rohingya men, women, and children moving toward a future that did not yet exist. Fawaz submitted the work to the Guanlan Print Biennale in China, half-expecting rejection. Instead, it was accepted, archived, celebrated and later awarded internationally.

“That’s when I understood,” he reflects, “governments are one thing. But artists, regardless of Geography, speak a universal language.”

He places himself in a lineage shaped by images that changed history: Zainul Abedin’s famine sketches, Qamrul Hasan’s Annihilate These Demons during the Liberation War. These were not artworks made for approval; they were acts of courage. Fawaz walks that same path. When anti-semitism surged, he created The Monument. When Kamalapur Station faced destruction, he responded with Save Kamalapur.’ When the legacy of 1971 was questioned, he made For Our Next Generation. For him, art is never neutral. It is a responsibility carried forward.

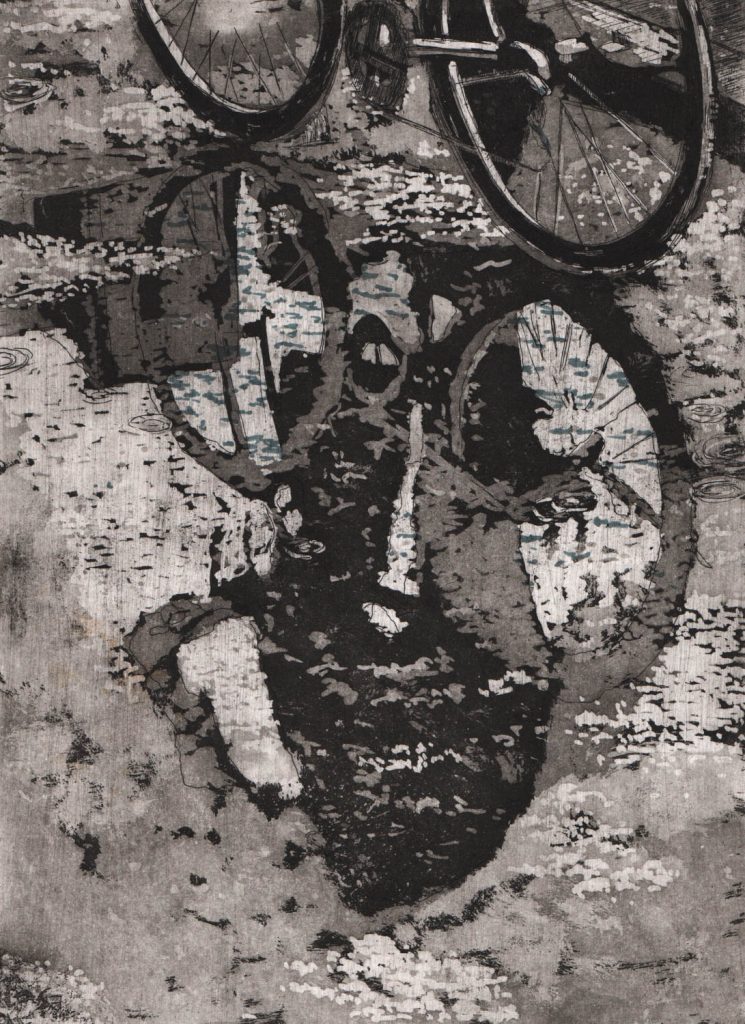

Fawaz’s return to academia in his late forties, joining Charukola for an MFA, was transformative, humbling, and occasionally hilarious. He created a self-portrait titled Charukola’s Gadha (The Donkey of Charukola), a satirical reflection on the chaos and beauty of art education. His Charukola series is a tribute to Architect Mazharul Islam, whose 1953 design for the Faculty of Fine Arts still whispers inspiration through its courtyards, voids, and spiralling staircases. Fawaz translates that architecture into print, turning structure into memory, space into poetry.

Though trained as an architect and having spent years as a professor, Fawaz ultimately found his true home in intaglio printmaking, a discipline as demanding as it is unforgiving. Acid baths, metal plates, ink, pressure, repetition. It is slow. Expensive. Punishing. And perfectly suited to his temperament. Printmaking has taken him from Paris to Venice, from Zagreb to Budapest.

He has worked through nights in near-abandoned studios where, he says, “angels and demons walk with you when it rains.” Every line he carves carries obsession, restraint, and quiet tension.

He is the first Bangladeshi artist to be published in the California Journal of Printmakers, and his works now reside in prestigious international archives, including the International Printmaking Museum in China.

Yet despite global recognition, Fawaz insists he is only beginning. He believes his most important work lies ahead, perhaps in his sixties or seventies, like Hokusai or Matisse. He continues to unlearn, to question, to dismantle certainty.

His wife and daughter are his quiet anchors. Dhaka remains his restless muse. ALEF Studio is his creative refuge. And printmaking, messy, obsessive, merciless, remains his lifelong companion.

In his artist’s note, Fawaz describes his journey as a “miseducation” of years learning alone through books, YouTube, trial, and stubborn persistence. When he finally entered Charukola, he realised not how little he knew, but how infinite art truly is. He laughs at himself, at awards, at the pretensions of the art world. But beneath the humour lives a relentless devotion.

He says, “I haven’t decided what my art means. But I’m learning what to avoid.

In an age of thin attention and exhausted empathy, Fawaz Rob’s work asks us to slow down. To remember. To feel. He reminds us that tragedies are not content, and justice is not optional. That art is not only seen, it is also carried, walked with. And sometimes, like the figures in Long Walk Home, art is what keeps us moving forward toward a home we have not yet reached, but still believe in.