For Bangladeshi artist Dhananjoy Mondal, art has always been a river—flowing, shifting, unpredictable, and deeply connected to the soil that raised him. A painter of rivers, fields, and rural life, his work is as much about colours on canvas as it is about memory, patience, and belonging. Over the decades, Mondal has carved out a career not only as an accomplished painter working in watercolour and acrylics, but also as a dedicated teacher shaping generations of young artists at Seabreeze International School. His journey tells a story of evolution, but also of constancy: no matter how far his brush has traveled, it always returns to the waters of his childhood.

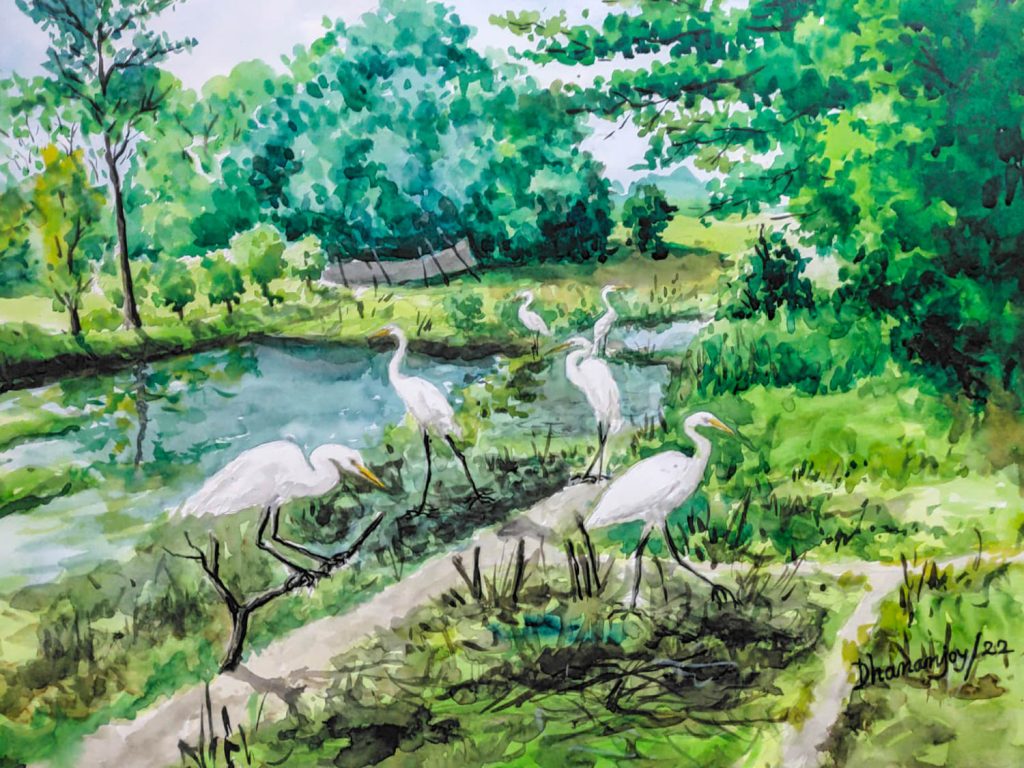

Mondal grew up in Luxmibilas, a small village in Munshiganj, where nature itself was his first teacher. Rivers, changing seasons, and the lush green life left behind by water shaped his sense of aesthetics long before he set foot in a studio. His first encounter with art wasn’t in an academic classroom, but in a kumarbari—a potter’s house—where he watched colours and forms emerge from clay molded by hand. “I am still that curious boy from Luxmibilas,” he says, reflecting on his journey. “Even with gray hair today

I am painting the same rivers, fields, and boats that fascinated me as a child.”

This grounding in nature and rural life has remained a constant, no matter how his mediums and techniques evolved with time. During his undergraduate years at the Faculty of Fine Arts, University of Dhaka, watercolour was his primary medium. Acrylics had not yet made their way into local art supply shops. But in 1992, Mondal encountered acrylic paint for the first time, and it changed his practice forever. “Technically, both watercolour and acrylic rely on water as a solvent, which made them easy to adapt to,” he explains. “But each has its own nature

as a solvent, which made them easy to adapt to,” he explains. “But each has its own nature. Watercolour is like a river—you can guide it, but never fully control it. Acrylic is forgiving, you can layer and rework endlessly. Together, they keep me balanced between patience and freedom.”

Even after decades of painting, Mondal insists the thrill of watching colours interact with water is something that never grows old. Every artist has a mentor, and for Mondal, it wasn’t a famous name from Charukola but a humble figure from his childhood: Paul Gomes, his primary school teacher. Gomes introduced the young boy to painting, from pottery decorations to charcoal sketches, laying the foundation that still guides him today. “I owe him my start,” Mondal reflects. “He made me see that art could be more than just a pastime—it could be a way of life.” For the past 15 years, Mondal has taught art at Seabreeze International School, guiding O Level and A Level students. Teaching, he says, has profoundly shaped his own practice. “Teaching keeps me young,” he smiles. “Every student sees the world differently. Their mistakes, their bold choices, their unfiltered curiosity—they remind me that art is never stagnant. Sometimes I even have to unlearn what I thought I knew.” Mondal is known for nurturing confidence in students who doubt their artistic ability.

His classroom motto is simple: “There is no wrong line in art, only a new possibility.

By painting alongside his students, he shows them how a blotch can transform into a flower or a river. One memory still stands out. “A student once painted a rainy village scene entirely in shades of blue,” he recalls. “At first, I thought it was a mistake. But when I stepped back, I saw he had captured the melancholy of the monsoon in a way I’d never imagined. That day, I realized even a child’s instinct can teach a seasoned artist something new.” If there is one subject that Mondal returns to endlessly, it is the river. Born in a riverine land, he feels water is part of his soul. “Sometimes it flows calmly, sometimes it storms like the Padma.

Every time I paint it, the river reflects my own shifting moods.

Rivers also connect his personal journey to the collective identity of Bangladesh, where waterways have shaped livelihoods, memories, and art across centuries.

Though Mondal teaches realism as a foundation for his students, he has also explored abstraction in his own career. “Experimentation keeps an artist alive,” he says. His abstract phase gave him freedom with colour and form, though in recent years, he has returned to refining his acrylic work. He believes experimentation is not about abandoning tradition, but about pushing boundaries.

Art must evolve, but roots keep it grounded

He reflects. Mondal’s works often carry the unmistakable touch of Bangladeshi heritage. The curve of a fishing boat, the hues of rice fields, the rhythm of rural life—they appear naturally in his art. Even in abstraction, fragments of Bengal slip through his strokes. “It isn’t deliberate,” he admits. “It’s simply who I am. My roots are my palette.” He sees watercolour as carrying a nostalgic charm—reminding people of rainy days, boats, and paddy fields—while acrylic represents a bold, modern voice. Together, they mirror Bangladesh’s dual identity: memory and modernity, tradition and transformation. In a globalized art world, Bangladeshi artists are finding both opportunities and challenges. Mondal acknowledges the double-edged sword: “Global exposure gives us new techniques and recognition, but it also tempts some to imitate too much.

The strongest artists absorb the world but filter it through the soil of Bengal. That balance gives our art its true voice.

Over the decads, Mondal’s works have found their way into prestigious exhibitions both at home and abroad. His journey began with the Annual Art Exhibitions at the Faculty of Fine Arts, University of Dhaka, between 1979 and 1981, where he first gained recognition as a promising young painter. His first solo exhibition came in 1986 at the Academy of Fine Arts North Gallery in Kolkata, marking his emergence on an international stage.

From group shows like the Exhibition for Flood Relief at Bishwo Shahitto Kendra (1988) to the Class of 1979 showcase at Cosmos Gallery (2012), Mondal has remained connected to the artistic community that shaped him. More recently, he participated in the 3rd, 2nd, and 1st exhibitions of the ‘79 batch of Charukala at Zainul Gallery, Faculty of Fine Arts, University of Dhaka (2018–2020), and in 2022, his works were featured at the 3rd International Competition and Exhibition of Painting and Sculpture at the Nandalal Bose Art Gallery, Indian Council for Cultural Relations, Kolkata. These exhibitions not only highlight his longevity but also the consistency of his vision—a river that has never ceased to flow. Alongside exhibitions, Mondal’s work has earned him numerous awards. In the early 1980s, he won prizes for both watercolour (1981) and oil painting (1983) at Dhaka University’s Faculty of Fine Arts. Decades later, his mastery continued to be recognized with first prizes at the Annual Art Exhibition of Lyra Stationery in 2018 and 2019. Such accolades span nearly four decades, underscoring a career rooted in both resilience and renewal. If there is one lesson Mondal values above all, it is patience. “Without patience, art becomes decoration. True art takes time—to see, to feel, to let the canvas speak back.” He often leaves a painting leaning against the wall for days, returning only when he feels at peace. That is when he knows it is complete. When facing creative blocks, Mondal returns to nature: a walk by the river, sitting under a tree, watching the light shift on water. With his students, he uses play—asking them to paint with their non-dominant hand, or even with eyes closed—to help them let go of fear. Among his many works, one series changed Mondal deeply: a cycle of paintings on abandoned boats. At first, they seemed like ordinary landscapes, but as he painted, the boats became metaphors for decay, resilience, and survival. “That series taught me that art doesn’t only capture beauty. It can hold emptiness and silence too. Sometimes what is absent speaks louder than what is present.”Despite decades of painting and teaching, Mondal’s dreams are far from complete. He hopes one day to create a large-scale mural of Bangladesh through its rivers—a flowing narrative from rural simplicity to urban chaos, from tradition to globalization. “It is a daunting challenge,” he admits, “but one that still lives in my heart.” When asked what he hopes his students carry forward, Mondal doesn’t speak of fame and mastery. Instead, he hopes they leave with sharper eyes—for details, for beauty and for humanity. “Technique can be taught,” he says, “but learning to see—that is art’s true gift.” As both painter and teacher, Dhananjoy Mondal embodies the river he so often paints: flowing through generations, carrying fragments of memory, and nourishing the ground it touches.

His work reminds us that art is not only about colours on a canvas, but about patience, humility, and the quiet strength of roots.

And just like the rivers of Bangladesh, his art keeps moving forward—alive, ever-changing, yet always carrying the essence of home.